POOL

In this article, we’re going to look at POOL, a handy “little language” I recently created for templating object-oriented modules. Now you may not write many object-oriented modules, so this may not sound too interesting to you. Don’t worry; I also plan to discuss, among other things, Ruby, how to use the Template Toolkit, profiling, computational linguistic trie structures, Ruby again, and the oil paintings of the Great Masters. Hopefully, something in here will be enough to keep your interest.

Splashing Around

One of the reasons that I always feel I never get anything substantial done in Perl is that I’m always distracted unduly by subtasks, particularly metaprogramming. I write so many “labor-saving” modules that I never get around to doing the original labor in the first place.

For instance, I wanted to write something to handle my accounts; I needed something to handle command-line options but I couldn’t be bothered with the Getopt::Long rigmarole, so I wrote Getopt::Auto. Next, I needed to parse a simple configuration file and I couldn’t face writing yet another colon-separated file parser, so I wrote Config::Auto. Finally, I wrote something that examined a database schema and wrote Class::DBI packages for each table – all helpful tasks, and they meant I would never have to worry about configuration files or command-line options again. But, of course, I forgot about my accounts-handling application.

Something like this happened again recently. I started writing a module I’m calling Devel::DProfPP, which parses the data output by Devel::DProf in a neat object-oriented way. I was about five minutes into it when found myself writing:

=head1 CONSTRUCTOR

$object = Devel::DProfPP->new( %options )

Creates a new C<Devel::DProfPP> instance.

=

sub new {

my ($class, %opts) = @_;

bless { %opts }, $class;

}

And then I wrote my test: (I’m a bad boy, I write my tests after I write the code)

use Test::More;

use_ok("Devel::DProfPP");

my $x = Devel::DProfPP->new();

isa_ok($x, "Devel::DProfPP");

...

Nothing strange about that, you might think. It’s something I’ve written a dozen of times before, and something I will probably write a dozen times again. And that’s when it hit me. I don’t want to spend my time pounding out constructors and accessors, documentation that’s practically identical from class to class, tests that are eminently predictable, and I never, ever wanted to have to write my $self = shift; again.

There are two ways to solve this. Now I’m not going to last long as editor of perl.com if I suggest everyone should do the first, and switching to Ruby wouldn’t help with the documentation and tests part of the problem anyway.

The second is, of course, to make the computer do the hard work. I sketched out a short description of what I wanted in my Devel::DProfPP module, and wrote a little parser to read in that description, and then had some code generate the module. Then, I made a critical decision. I had just been doing some work with Template Toolkit, and wanted some more opportunity to play with it. So instead of hard-coding what the output module ought to look like, I simply passed the parsed data structure to a bunch of templates and let them do the work. This gave me an amazing amount of flexibility in terms of styling the output, and that’s where I think the power of this system, the Perl Object Oriented Language, (POOL) lies.

In order to investigate that, let’s look at some POOL files and the output they generate, and then we’ll examine how the templates work and fit together.

Diving In

The POOL language is very, very ad hoc. It’s bizarre and inconsistent, but that’s because it was created by rationalizing a module description I scribbled down late one night. But it does the job. It’s essentially a brain dump, and if your brain happens not to work like mine, then you might not like it; if yours does work like mine, my commiserations.

The POOL distribution, available from CPAN, ships with a handy reference manual, and that very description; these are the original notes I made when I was mocking up Devel::DProfPP, and they look like this:

Devel::DProfPP - Parse C<Devel::DProf> output

DESCRIPTION

This module takes the output file from L<Devel::DProf> (typically

F<tmon.out>) and parses it into a Perl data structure. Additionally, it

can be used in an event-driven style to produce reports more

immediately.

EOD

@fh

->@enter || sub {}

->@leave || sub {}

ro->@stack []

@syms []

parse

top_frame ->stack->[0]

The first line should be familiar to anyone who writes or uses Perl modules: it’s the description line that goes at the top of the documentation. It’s enough to identify the class name and provide some documentation about it.

The next thing is the module description, again for the documentation, which begins with DESCRIPTION and ends with EOD.

When you look at the things starting with @, don’t think Perl, think Ruby - they’re not arrays, they’re instance variables. Our Devel::DProfPP object will contain a filehandle to read the profiling data from, a subroutine reference for what to do when we enter a subroutine and when we leave one, the current Perl stack, and an array of symbols to hold the subroutine names.

These instance variables come in three types. The first are variables that the user doesn’t set, but come with every new instance. I call these “set” variables, because they’re come set to a particular value. Then there are “defaulting” instance variables, which the user may specify but otherwise default to a particular value. And then there are just ordinary ones, which are not initialized at all. Thankfully for me, the Devel::DProfPP brain dump contained all three types.

The symbol table and the stack are “set” variables. They come set to the an empty array reference; we signify this by simply putting an empty array reference on the same line.

@syms []

The enter subroutine, on the other hand, is a defaulting variable. (Don’t worry about the arrow for now.) If the user doesn’t specify an action to be performed when the profiler says that a subroutine has been entered, then we want to default to a coderef that does nothing.

In Perl, when we want to default to a value, we say something like:

$object->{enter} = $args{enter} || sub {};

So the POOL encoding of that is:

@enter || sub {}

Finally, there’s the filehandle, which the user supplies. Nothing special has to occur for this instance variable, so we just name it:

@fh

From this, we know enough to create a constructor like so:

sub new {

my $class = shift;

my %args = @_;

my $self = bless {

fh => $args{fh},

enter => $args{enter} || sub {},

leave => $args{leave} || sub {},

syms => [],

stack => [],

}, $class;

return $self;

}

And that’s precisely what POOL does. After the constructor, comes the accessors; we want to be able to say $obj->enter to retrieve the on-enter action, for instance. This thought led naturally to the syntax

->@enter || sub {}

When POOL sees an arrow attached to an instance variable, it creates an accessor for it:

sub enter {

my $self = shift;

if (defined @_) { $self->{enter} = @_ };

return $self->{enter};

}

The stack accessor is an interesting one. First, we only want this to be an accessor and not a mutator – we really don’t want people modifying the profiler’s idea of the stack behind its back. This is signified by the letters ro (read-only) before the accessor arrow.

ro->@stack []

A further twist comes from the fact that POOL is still trying to DWIM around my brain and my brain expects POOL to be very clever indeed. Because we have declared stack to be set to an array reference, we know that the stack accessor deals with arrays. Hence, when $obj->stack is called, it should know to dereference the reference and return a list. This means the code ends up looking like this:

sub stack {

my $self = shift;

return @{$self->{stack}};

}

Aside from constructors and accessors, POOL knows about two other styles of method. (For now; there are more coming.) There are ordinary methods, which are simply named:

parse

Sadly we can’t DWIM the entire code for this method, so we generate the best we can:

sub parse {

my $self = shift;

#...

}

And the final style is the delegate. The sad thing about the delegate given in the DProfPP example is that it doesn’t actually work, but we’ll pretend that it does. Delegates are useful when you have an object that contains another object; you can provide a method in your class that simply diverts off to the contained object. For instance, if we have a class representing a mail message, then we may wish to store the head and body as separate objects inside our main object. (Mail::Internet does something like this, containing a Mail::Header object.) Now we can provide a method called get_header, which simply locates the header object and passes on its arguments to that:

sub get_header {

my $self = shift;

$self->header->get(@_);

}

In POOL lingo, this is a delegate via the header method, and get tells us how to do the delegation. It would be specified like this:

get_header ->header->get

Notice that this is precisely what appears in the middle of the Perl code for this method. An additional feature is that the “how” part of the delegation is optional. If we were happy for our top-level method to be called get instead of get_header, then we could say:

get ->header->

To me, this symbolizes going “through” the header method in order to call the get method.

These are the basics of the POOL language, and we’ve seen a little of the code it generates. It also generates a full set of documentation and tests, as well as a MANIFEST file and Makefile.PL or Build.PL file, but we’ll look at those a little later.

In case you’re interested, the reason why the delegation in the example doesn’t work is because I was being too clever. I thought I could say:

top_frame ->stack->[0]

and have a top_frame method which “calls” [0] on the stack array reference, returning its first entry. This doesn’t work for two reasons. First, I was too clever about ->stack and now it returns a list instead of an array reference. Second, delegates need to pass arguments, so POOL ends up generating code that looks like:

return $self->stack->[0](@_);

(The third reason, of course, is that the top of the stack when represented as an array is element -1, not element 0. Oops.)

I thought about fixing this to do what I really, really mean, but decided that would be too nasty.

Another Example

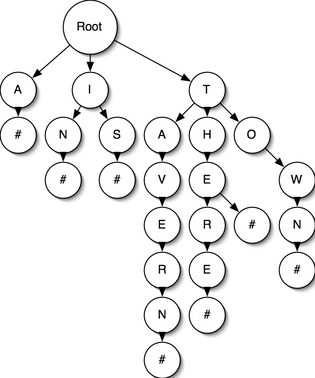

Now that I had this neat tool for generating modules, I set it to work on the next module I wrote; this was a variant of Tree::Trie, a class to represent the trie data structure. Tries are a handy way of representing prefix and suffix relationships between words. They’re conceptually simple; each letter in a word is inserted into a tree as the child of the previous letter. If we wanted a trie to count the prefices in the phrase THERE IS A TAVERN IN THE TOWN, then we would first insert the chain T-H-E-R-E-#, then I-S-#, then A-#, and so on, where # represents “end-of-word”. We’d end up with a trie looking like this:

|

| Figure 1: An Example of a Trie |

Tree::Trie is good at this sort of thing, but it didn’t do a few extra things I needed, so I wrote an internal-use module called Kasei::Trie; this was the POOL file I used to generate it:

Kasei::Trie - Implement the trie data structure

DESCRIPTION

"Trie"s are compact tree-like representations of multiple words, where

each successive letter is introduced as the child of the previous.

EOD

@children {}

insert

Kasei::Trie::Node

@children

->@data

The main class, Kasei::Trie, has a constructor with one instance variable that is initialized to be an empty hash reference, and one method, insert. There’s also a secondary class representing each node in the trie, which has its own children, and has a data variable with its own accessor.

After generating this with POOL, all I needed to do was to fill in the code for the insert method, and modify some tests. A manifest, Makefile.PL, test suite with nine tests, and 161 lines of code and documentation were automatically created for me. I suspect that POOL saved me one to two hours.

The High Dive

Let’s now take a look at the templates that make this all happen. The main template is called module, and it looks like this:

package [% module.package %];

[% INCLUDE module_header %]

=head1 SYNOPSIS

[% INCLUDE synopsis %]

=head1 DESCRIPTION

[% module.description %]

=head1 METHODS

[%

FOREACH method = module.methods;

INCLUDE do_method;

END

%]

[% INCLUDE module_footer %]

1;

As you can probably guess, in the Template Toolkit language, interesting things happen between [% and %]. Everything else is just output wholesale, but all kinds of things can happen inside the brackets. The first thing that happens is that we look at the module’s package name. All the data we’ve collated from the parsing phase is stuffed into a hash reference, which we have passed into the template as module. The dot operator in Template Toolkit is a general do-the-right-thing operator that can be a method call, a hash reference look-up or an array reference look-up. In this case, it’s a hash reference look-up, and we perform the equivalent of $module->{package} to extract the name.

Template Toolkit’s [% INCLUDE template %] directive looks for the file template in its template path, processes it passing in all the relevant variables, and includes its output. So after the initial package ...; line, we include another template that contains everything that goes at the top of the module. As we’ll see later, part of the beauty of templating things this way is that you can override templates by placing your own idea of what should go at the top of a module into your private version of module_header earlier in the template path, in a sense “inheriting” from the base set of templates.

Similarly, we include a file that will output the synopsis, and output the description that we collected between the DESCRIPTION and EOD lines of our POOL definition file.

Next, we want to document the various methods and output the code for them. POOL will have placed all the metadata for the methods we’ve defined, plus a constructor, in the appropriate order in the methods hash entry of module. As this is an array reference, we want to use a foreach-style loop to look at each method in turn. Not surprisingly, Template Toolkit’s foreach-style loop is called FOREACH.

So this code:

[%

FOREACH method = module.methods;

INCLUDE do_method;

END

%]

will set a variable called method to each method in the array, and then call the do_method template. This simply dispatches to appropriate templates for each type of method. For instance, there’s the set of templates for the “delegate” style; delegate_code looks like this:

sub [% method.name %] {

my $self = shift;

return $self->[% method.via %]->[% method.how %](@_);

}

Whereas the documentation template contains some generic commentary:

=head2 [% method.name %]

[% INCLUDE delegate_synopsis -%]

Delegates to the [%method.how%] method of this object's [%method.via%].

=cut

The synopsis that appears in the documentation here and in the synopsis at the top of the file simply explains how the delegation is done:

$self->[% method.name %](...); # $self->[% method.via %]->[%method.how%]

Of course, there are some templates that are a little more complex, particularly those that generate the tests, but the main thing is that you can override any or none of those. If you don’t like the standard same-terms-as-Perl-itself licensing block that appears at the end of the module, then create a file called ~/.pool/license containing:

=head1 LICENSE

This module is licensed under the Crowley Public License: do what thou

wilt shall be the whole of the license.

POOL will pick up this template and use it instead of the standard one.

There’s No P in Our POOL

When I started planning this article in the bath this morning, I realized that POOL is actually fantastically badly named; there’s nothing actually Perl-specific about the language itself, and it’s a handy definition language for any object-oriented system. Hence, I hereby retroactively name the project “the POOL Object Oriented Language”, which also satisfies the recursive acronym freaks. But can we, using the same parser and templating system, turn POOL files into other languages? Of course we can; this is all part of the flexibility of the Template Toolkit system. What’s more, we don’t even have to override all of the templates in order to do so, just some of them. For instance, here’s a Ruby equivalent of accessor_code:

[% IF method.ro == "ro"; %]

attr_reader :[% method.name %]

[% ELSE; %]

attr_accessor :[% method.name %]

[% END; %]

do_method and module_footer, however, never need to change, since all they do is include other methods. With a complete set of toolkits, the same POOL description can be used to output a Perl, Ruby, Python, Java and C++ implementation of a given class.

Going Deeper

When Frans Hals’ famous painting “The Laughing Cavalier” was being examined in a museum’s labs, someone had the bright idea of putting it through an X-ray machine. When they did this, they were amazed to find underneath the famous painting a completely different work – a painting of a young girl. They then adjusted the settings on the X-ray machine and tried again, and underneath the young girl, they found another painting. Since then, it’s been common practice to X-ray pictures, and art historians have found many layers of paint underneath some of the most-famous pictures.

What’s this got to do with POOL? Well, very little, but I wanted to throw that in. Since I realised that POOL’s templates can be inherited so easily, I’ve had the idea of POOL “flavors”; coherent sets of templates that can be layered like oil paintings to impart certain properties to the output.

For instance, at the moment, POOL outputs unit tests in separate files in the t/ directory, one for each class. Some people, however, prefer to have their tests in the module right alongside the documentation and implementation, using the method described in Test::Inline. Well, there’s no reason why POOL shouldn’t be able to support this. All you’d need to do is create a new directory, let’s say testinline/, and put a modified version of do_method in there which says something like:

[% INCLUDE method_pod %]

=head2 begin testing

[% INCLUDE method_test %]

=cut

[% INCLUDE method_code %]

Next, arrange for testinline/ to appear in the Template Toolkit template path, and magically your tests will appear in the right place.

It’s not inconcievable that multiple “flavours” could combine in order to theme a module; for instance, you might want a module which uses Test::Class for its tests, and Module::Build for its build file, with a BSD license flavor and Class::Accessor for its accessors instead of having them explicitly coded. Conceptually, you’d then say:

pool --flavours=testclass,modulebuild,bsdlicense,classaccessor mymodule.pool

and the module would come out just as you want. This hasn’t happened yet for two reasons: First, although it’s only a two- or three-line change to the pool parser to support pushing these directories onto the template path, I haven’t needed it yet so I haven’t done it, and second, because I haven’t written any flavors yet. But it’s easy enough to do.

Other future directions for POOL include a syntax for class methods and class variables, support for other languages as mentioned about, (which basically means ripping out the hard-coding of MANIFEST, Makefile.PL and so on and replacing that with a more flexible method) and other minor modifications. For instance, I’d like some syntax to specify dependencies; other Perl modules which will then be use’d in the main modules and which would be named at the appropriate place in the Makefile.PL. And, of course, there’s building up a library of flavors, including “total conversion” flavors like Ruby and Python.

The one thing that’s becoming really, really important is the need for nondestructive editing – the ability to fill in some additional code for a method, then regenerate the class from a slight change to the POOL file without losing the new method’s code. I’m going to need to add that soon to allow for iterative redesigning of modules.

But the main thing about POOL is what it does now – it saves me time, and it takes away the drudgery of writing OO classes in Perl.

And I will finish Devel::DProfPP soon. I promise.

Tags

Feedback

Something wrong with this article? Help us out by opening an issue or pull request on GitHub