The Hijacking of Perl.com

For a week we lost control of the Perl.com domain. Now that the incident has died down, we can explain some of what happened and how we handled it. This incident only affected the domain ownership of Perl.com and there was no other compromise of community resources. This website was still there, but DNS was handing out different IP numbers.

First, this wasn’t an issue of not renewing the domain. That would have been a better situation for us because there’s a grace period.

Second, to be very clear, I’m just an editor for the website that uses the Perl.com domain. This means that I’m not actually the “injured party” in legal terms. Tom Christiansen is the domain registrant, and should legal matters progress, there’s no reason for me, nor anyone else, to know all of the details. However, I’ve talked to many of the people involved in the process.

The incident response

I think we did a pretty good job with the decentralized, volunteer incident response, so I’d like to share part of what we did as I tell you the story. You may have had the pleasure (or pain) of a formal response, and there are various things you can do to forego extra headaches and frustration.

Early on the morning of January 27, the Perl NOC noticed through normal monitoring that something was wrong with the domain. Along with that, people started to report that the website had gone missing. As DNS updated across the globe, more and more people reported problems. We didn’t know what was happening or why.

Behind the scenes I started to collect incident information, and I put out a tweet asking for help. At this point we didn’t know what was going on; we just knew the effect. It’s important during the early stages of a response to verify what’s known and what’s rumor, and to separate who knows something and who’s passing around rumors. As with most situations, it’s that rumor group that dominates the conversation and they often have a more interesting story to tell because they can speculate and fabricate any narrative they like. Work the problem without speculation—find out what you actually know and what’s just a guess.

I started a Google doc and invited the relevant people. We started to fill in the details, classifying everything according with either green, amber, or red. Green was high confidence information, such as direct communication with a registrar, amber was likely good but unverified, and red was just flat out wrong. All information was tagged with a time and source. The first rule of rumor control is stating who you heard it from and when. Once this is in the document, other people know if what they think they know is better or more recent. And, sometimes the information that we thought was good turns out to be wrong. In those cases we update the document.

We also listed things that needed to happen, and various people picked up what they could address. For example, we started to check other community resources, so Elaine Ashton looked at the registration for cpan.org, which had an oddity in its contact info but later turned out to be fine after she dealt with the registrar on the phone. Robert Spier, part of the Perl NOC, was able to verify various network aspects, timelines, and so on. Rik Signes stepped up to set up a private mailing list on TopicBox (he is the CTO, after all). The trick here is to not do work that someone else can do for you (and often better than you can). Likewise, if someone is already doing something, you’re wasting your time (and others’ time) by redoing or reinventing it. Decentralization is fine, but someone needs to be the coordinator. In this case that turned out to be me because I had a lot invested in the Perl.com website, and I could easily work with Tom because we worked with each other for a year on Programming Perl.

My tweet and my reddit comments got the attention of both sides of the registrar equation, so I was talking to both Network Solutions and Key Systems very early in the process. We were very fortunate to that Perl is a known thing and that both Tom Christiansen and I are well-known within Perl. The first rule to success is to already be successful. People inside various organizations involved offered us help and guidance. Other victims were not so fortunate and help for them was not forthcoming. And, at some point, Perl was probably running those organizations, so there’s some fondness for the good ol’ days.

Mostly, I helped both sides get in touch with Tom Christiansen and helped him manage all the players. In many incidents, people become overwhelmed by everything that needs to happen and end up not doing anything. He needed to work with the registrars, so I took what work I could off his plate so he could focus on that bit.

We had learned very quickly that when you use the registered domain for your email contact, no one can contact you when that domain no longer handles your mail. Most of that hassle was verifying that people were who they say they are, but in the domain business, everyone knows who the real people are—this is what they do every day. We made sure that we didn’t overload them with inquiries from several different people asking the same question. Coordinating who is working with whom avoids the N-squared communication issues and lets people do the work they need to do rather than answer the same questions repeatedly.

Once everyone who needed to talk to each other had good contact info, the process mostly took care of itself. We didn’t know that everything would work out, but as the situation developed we became more confident that it would. Our confidence, however, isn’t reportable information. You don’t announce what you think will happen or what is promised to happen because often there are delays or hiccups.

We transitioned to managing public information and sharing what we could. Our goal was to give people the confidence that they had the right info. As a techy audience, we often like to have all the information, but there’s very little that anyone actually needs to know.

We settled on having all the updated info in one place, at The Perl NOC blog. Sometimes we knew things several hours before we published the information because we did the extra work to directly verify things. People didn’t have to track social media, etc to find out what was going on because they could remember this one place. We still broadcast updates all over the place, but always pointed back to the NOC blog. A single point of reference is very helpful.

For those in the incident response, we developed a current situation summary and talking points. These were basically the things that we had verified that we could disclose without compromising the legal process.

We also tracked people and stories. Who’s who at various companies, which reporters are writing about the incident, and what discussion threads are out there. Some people in various discussion threads were obviously just there for the lulz, while others had good or actionable details (which often means they are on the inside of the situation). Again, we used the green / amber / red categories.

This isn’t my first rodeo, and I stepped into the role of press contact. Despite our diligent work to verify everything, many outside people just made up stuff. That’s just how it is and I expected that. The publishing maxim “If your mother says she loves you, get a second source” doesn’t apply in the age of Twitter. You don’t even need the first source.

It’s important to have one face (mouth?) to represent the diligent work everyone was doing. Half the “news” stories didn’t do basic research, and some of those reporters don’t even have contact info (really, a reporter you can’t contact?). A few were able to correct their stories after talking to me.

The Register had spot on reporting from the start as did Paul Ducklin at Sophos.

About a week after the nameservers changed, I had settled into the idea that it could take several weeks to unravel the hijacking. With multiple countries involved along with various sets of laws and rules in effect, things might have a much slower pace than we’d like. In the internet age, tomorrow is basically infinitely far away. David Farrell floated the idea of renaming the site, and we started using perldotcom.perl.org as a temporary domain. Robert was able to set that up quickly, and we even got some good work out of it as pull requests from the community found spots where we had hard-coded various things that we shouldn’t have (anyone can send a pull request for anything about the site!). The GitHub process that David had set up was key to making all of this work; it’s a pleasure to get even the tiniest pull requests from the community.

Then, in early February I got some solid (green) back-channel information that we’d get the domain back in a couple of days. I was dubious but it actually happened! Again, I think we were very fortunate here and that many people with a soft spot in their hearts for Perl did a lot of good work for us. All sides understood that Perl.com belonged to Tom and it was a simple matter of work to resolve it. A relatively unknown domain name might not fare as well in proving they own it.

Recovering the domain wasn’t the end of the response though. While the domain was compromised, various security products had blacklisted Perl.com and some DNS servers had sinkholed it. We figured that would naturally work itself out, so we didn’t immediately celebrate the return of Perl.com. We wanted it to be back for everyone. And, I think we’re fully back. However, if you have problems with the domain, please raise an issue so we at least know it’s not working for part of the internet.

What we think happened

This part veers into some speculation, and Perl.com wasn’t the only victim. We think that there was a social engineering attack on Network Solutions, including phony documents and so on. There’s no reason for Network Solutions to reveal anything to me (again, I’m not the injured party), but I did talk to other domain owners involved and this is the basic scheme they reported.

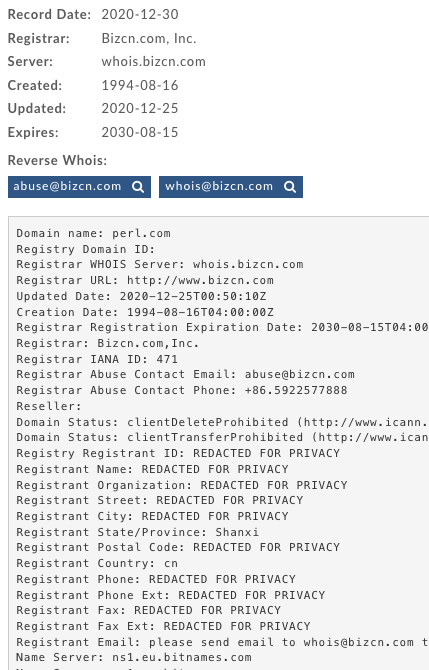

John Berryhill provided some forensic work in Twitter that showed the compromise actually happened in September. The domain was transferred to the BizCN registrar in December, but the nameservers were not changed. The domain was transferred again in January to another registrar, Key Systems, GmbH. This latency period avoids immediate detection, and bouncing the domain through a couple registrars makes the recovery much harder.

Notice the long lag time of the first transfer, though. The domain is compromised in September but transferred in December. There’s a reason for that: ICANN has a 60-day rule. You can’t transfer the domain within 60 days of updating the contact info. We think part of the attack changed the registration at the same time as the attackers renewed the domain for a couple more years past its original expiration in 2029.

Once transferred to Key Systems in late January, the new, fraudulent registrant listed the domain (along with others), on Afternic (a domain marketplace). If you had $190,000, you could have bought Perl.com. This was quickly de-listed after the The Register made inquiries.

Some lessons

Obviously this is an embarrassing situation, but it’s not an uncommon story. This domain was registered in the early 90s, Tom Christiansen was given control of it shortly after that, and basically kept paying the registration fees. Since it wasn’t a nagging problem, the domain was left as it was. Features such as two-factor authentication probably would have saved us much of this trouble (although social engineering attacks tend to route around safeguards).

I’ve already mentioned the problem with using the domain in the contacts for the domain. When there’s a problem, the communication channels are also borked. Have at least one of the contacts go somewhere else.

It’s essential to communicate with “one voice” else you risk sowing confusion with different messages, even if they’re saying the same thing. You also want to project confidence, and competence so that the information you do release is treated credibly; if different channels are releasing different updates, the risk of error increases. The Perl Foundation insisted on releasing their own update instead of using our prepared statement. And even though it was brief, the link to the Perl NOC blog was broken for several days. Don’t take unnecessary risks.

And, it always helps to have friends and good relationships with the people who are able to help. The people at Network Solutions and Key Systems were very helpful in the recovery, as were several other people who keep the internet working. I wish I could give them direct credit, but I’m sure they’d rather do their work quietly.

Where we are now

The Perl.com domain is back in the hands of Tom Christiansen and we’re working on the various security updates so this doesn’t happen again. The website is back to how it was and slightly shinier for the help we received.

As part of the incident response, The Perl Foundation Infrastructure Working Group surveyed other important community domains and will work to secure those. If you are interested in helping with that, get in touch with them.

Tags

brian d foy

brian d foy is a Perl trainer and writer, and a senior editor at Perl.com. He’s the author of Mastering Perl, Mojolicious Web Clients, Learning Perl Exercises, and co-author of Programming Perl, Learning Perl, Intermediate Perl and Effective Perl Programming.

Browse their articles

Feedback

Something wrong with this article? Help us out by opening an issue or pull request on GitHub