Don't Be Afraid to Drop the SOAP

SOAP has great hype; portable, simple, efficient, flexible, and open, SOAP has it all. According to many intelligent people, writing a web service with SOAP should be a snap, and the results will speak for themselves. So they do, although what they have to say isn’t pretty.

Two years ago I added a SOAP interface to the Bricolage open source content management system. I had high expectations. SOAP would give me a flexible and efficient control system, one that would be easy to develop and simple to debug. What’s more, I’d be out on the leading edge of cool XML tech.

Unfortunately the results haven’t lived up to my hopes. The end result is fragile and a real resource hog. In this article I’ll explore what went wrong and why.

Last year, I led the development of a new content-management system called Krang, and I cut SOAP out of the mix. Instead, I created a custom XML file-format based on TAR. Performance is up, development costs are down, and debugging is a breeze. I’ll describe this system in detail at the end of the article.

What is SOAP?In case you've been out to lunch, SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol) is a relatively new RPC (Remote Procedure Call) system that works by exchanging XML messages over a network connection, usually over HTTP. In an RPC system, a server offers routines (procedures) that clients may call over a network connection. SOAP surpasses its direct predecessor, XML-RPC, with an enhanced type system and an improved error-handling system. Despite the name, SOAP is neither particularly simple nor object-oriented. |

Bricolage Gets SOAP

When I joined the Bricolage project, it lacked a good way to control the application aside from the browser-based GUI. In particular, we needed a way to import data and trigger publish runs. Bricolage is a network application, and some useful tasks require interaction with multiple Bricolage servers. SOAP seemed like an obvious choice. I read “Programming Web Services with Perl” and I was ready to go.

I implemented the Bricolage SOAP interface as a set of classes that map SOAP requests to method calls on the underlying objects, with some glue code to handle XML serialization and deserialization. I used XML Schema to describe an XML vocabulary for each object type, which we used to validate input and output for the SOAP methods during testing.

By far the most important use-case for this new system was data import. Many of our customers were already using content management systems (CMSs) and we needed to move their data into Bricolage. A typical migration involved processing a database dump from the client’s old system and producing XML files to load in Bricolage via SOAP requests.

The SOAP interface could also move content from one system to another, most commonly when moving completed template changes into production. Finally, SOAP helped to automate publish runs and other system maintenance tasks.

To provide a user interface to the SOAP system, I wrote a command-line client called bric_soap. The bric_soap script is a sort of Swiss Army knife for the Bricolage SOAP interface; it can call any available method and pipe the results from command to command. For example, to find and export all the story objects with the word foo in their title:

$ bric_soap story list_ids --search "title=%foo%" |

bric_soap story export - > stories.xml

Later we wrote several single-purpose SOAP clients, including bric_republish for republishing stories and bric_dev_sync for moving templates and elements between systems.

What Went Right

- The well-documented XML format for Bricolage objects made developing data import systems straightforward. Compared to previous projects that attempted direct-to-SQL imports, the added layer of abstraction and validation was an advantage.

- The interface offered by the Bricolage SOAP classes is simpler and more regular than the underlying Bricolage object APIs. This, coupled with the versatile

bric_soapclient, allowed developers to easily script complex automations.

What Went Wrong

- SOAP is difficult to debug. The SOAP message format is verbose even by XML standards, and decoding it by hand is a great way to waste an afternoon. As a result, development took almost twice as long as anticipated.

- The fact that all requests happened live over the network further hampered debugging. Unless the user was careful to log debugging output to a file it was difficult to determine what went wrong.

- SOAP doesn’t handle large amounts of data well. This became immediately apparent as we tried to load a large data import in a single request. Since SOAP requires the entire request to travel in one XML document, SOAP implementations usually load the entire request into memory. This required us to split large jobs into multiple requests, reducing performance and making it impossible to run a complete import inside a transaction.

- SOAP, like all network services, requires authentication to be safe against remote attack. This means that each call to

bric_soaprequired at least two SOAP requests — one to login and receive a cookie and the second to call the requested method. Since the overhead of a SOAP request is sizable, this further slowed things down. Later we added a way to save the cookie between requests, which helped considerably. - Network problems affected operations that needed to access multiple machines, such as the program responsible for moving templates and elements —

bric_dev_sync. Requests would frequently timeout in the middle, sometimes leaving the target system in an inconsistent state. - At the time, there was no good Perl solution for validating object XML against an XML Schema at runtime. For testing purposes I hacked together a way to use a command-line verifier using Xerces/C++. Although not a deficiency in SOAP itself, not doing runtime validation led to bad data passing through the SOAP interface and ending up in the database where we often had to perform manual cleanup.

Round Two: Krang

When I started development on Krang, our new content management system, I wanted to find a better way to meet our data import and automation needs. After searching in vain for better SOAP techniques, I realized that the problems were largely inherent in SOAP itself. SOAP is a network system, tuned for small messages and it carries with it complexity that resists easy debugging.

On the other hand, when I considered the XML aspects of the Bricolage system, I found little to dislike. XML is easy to understand and is sufficiently flexible to represent all the data handled by the system. In particular, I wanted to reuse my hard-won XML Schema writing skills, although I knew that I’d need runtime validation.

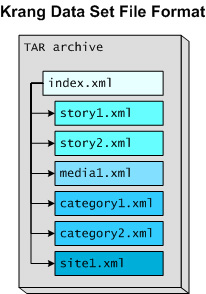

In designing the new system I took a big step back from the leading edge. I based the new system on the TAR archive file format, which dates back to the mid-70s!

*Figure 1.*

*Figure 1.*

I named the file format “Krang Data Set” (KDS). A KDS file is a TAR archive containing a set of XML files. A special file, index.xml, contains data about all the files contained in the KDS file, providing class names and IDs. To reduce their size, it’s possible to compress KDS files using gzip.

I wrote two scripts, krang_import and krang_export, to read and write KDS files. Each object type has its own XML Schema document describing its structure. Krang classes implement their own deserialize_xml() and serialize_xml() methods. For example, to export all templates into a file called templates.kds:

$ krang_export --templates --output templates.kds

To import those templates, possibly on a different machine:

$ krang_import templates.kds

If the object being exported has any dependencies, the KDS file will include them. In this way a KDS file generated by krang_export is guaranteed to import successfully.

By using a disk-based system for importing and exporting data I cut the network completely out of the picture. This alone accomplishes a major reduction in complexity and a sizable performance increase. Recently we completed a very large import into Krang comprising 12,000 stories and 160,000 images. This took around 4 hours to complete, which may seem like a long time but it’s a big improvement over the 28 hours the same import required using SOAP and Bricolage!

For system automation such as running publish jobs from cron, I decided to code utilities directly to Krang’s Perl API. This means these tools must run on the target machine, but in practice this is usually how people used the Bricolage tools. When an operation must run across multiple machines, perhaps when moving templates from beta to production, the administrator simply uses scp to transfer the KDS files.

I also took the opportunity to write XML::Validator::Schema, a pure-Perl XML Schema validator. It’s far from complete, but it supports all the schema constructs I needed for Krang. This allows Krang to perform runtime schema validation on KDS files.

What Went Right

- The new system is fast. Operating on KDS files on disk is many times faster than SOAP network transfers.

- Capacity is practically unlimited. Since KDS files separate objects into individual XML files, Krang never has to load them all into memory at once. This means that a KDS file containing 10,000 objects is just as easy to process as one containing 10.

- Debugging is much easier. When an import fails the user simply sends me the KDS file and I can easily examine the XML files or attempt an import on my own system. I don’t have to wade through SOAP XML noise or try to replicate network operations to reproduce a bug. Separating each object into a single XML file made working on the data much easier because each file is small enough to load into Emacs.

- Runtime schema validation helps find bugs faster and prevents bad data from ending up in the database.

- Because Krang’s design accounted for the XML system from the start it has a much closer integration with the overall system. This gives it greater coverage and stability.

What Went Wrong

- Operations across multiple machines require the user to manually transfer KDS files across the network.

- Users who have developed expertise in using the Bricolage SOAP clients must learn a new technology.

Conclusion

SOAP isn’t a bad technology, but it does have limits. My experience developing a SOAP interface for Bricolage taught me some important lessons that I’ve tried to apply to Krang. So far the experiment is a success, but Krang is young and problems may take time to appear.

Does this mean you shouldn’t use SOAP for your next project? Not necessarily. It does mean that you should take a close look at your requirements and consider whether an alternative implementation would help you avoid some of the pitfalls I’ve described.

The best candidates for SOAP applications are lightweight network applications without significant performance requirements. If your application doesn’t absolutely require network interaction, or if it will deal with large amounts of data then you should avoid SOAP. Maybe you can use TAR instead!

Resources

- Krang

- Bricolage

- Bricolage SOAP documentation

- SOAP

- SOAP::Lite

- Xerces/C++

- XML Schema

- XML::Validator::Schema

- Programming Web Services with Perl by Randy J. Ray and Pavel Kulchenko

Tags

Feedback

Something wrong with this article? Help us out by opening an issue or pull request on GitHub