State of the Onion 2003

This is the 7th annual State of the Perl Onion speech, wherein I tell you how Perl is doing. Perl is doing fine, thank you. Now that that’s out of the way, I’d like to spend the rest of the time telling jokes.

In fact, the conference organizers have noticed that I spend most of the time telling jokes. So each year they give me a little less time, so I have to chop out more of the serious subject matter so as to leave time for the jokes.

In fact, the conference organizers have noticed that I spend most of the time telling jokes. So each year they give me a little less time, so I have to chop out more of the serious subject matter so as to leave time for the jokes.

Extrapolating several years into the future, they’ll eventually chop my time down to ten seconds. I’ll have just enough time to say: “I’m really, really excited about what is happening with Perl this year. And I’d like to announce that, after lengthy negotiations, Guido and I have finally decided… <gong> [“Time’s up. Next speaker please”]

Well, you didn’t really want to know that anyway…

Since this is a State of the Union speech, or State of the Onion, in the particular case of Perl, I’m supposed to tell you what Perl’s current state is. But I already told you that the current state of Perl is just fine. Or at least as fine as it ever was. Maybe a little better.

But what you really want to know about is the future state of Perl. That’s nice. I don’t know much about the future of Perl. Nobody does. That’s part of the design of Perl 6. Since we’re designing it to be a mutable language, it will probably mutate. If I did know the future of Perl, and if I told you, you’d probably run away screaming.

As I was meditating on this subject, thinking about how I don’t know the future of Perl, and how you probably don’t want to know it anyway, I was reminded of a saying that I first saw posted in the 1960’s. You may feel like this on some days.

We the unwilling, led by the unknowing, are doing the impossible for the ungrateful. We have done so much for so long with so little We are now qualified to do anything with nothing

I think of it as the Blue-Collar Worker's Creed.

I think of it as the Blue-Collar Worker's Creed.

This has been attributed to various people, none of whom are Ben Franklin, Abraham Lincoln, or Mark Twain. My favorite attribution is to Mother Teresa. She may well have quoted it, but I don’t think she coined it, because I don’t think Mother Teresa thought of herself as “unwilling”. After all, Mother Teresa got a Nobel prize for being one of the most willing people on the face of the earth.

It’s also been attributed to the Marines in Vietnam, and it certainly fits a little better. But since I grew up in a Navy town, I’d like to think it was invented by a civilian shipyard worker working for the Navy. In any event, I first saw it posted in a work area at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard back in the 1960’s. Now, you may well wondering what I was doing in a Naval Shipyard in the 1960’s. That’s a secret.

Anyway, you may also be wondering why I brought it up at all. Well, last year I used the table of contents from an issue of Scientific American as my outline. This year I’d like to use this as my outline.

I’d like to, but I won’t.

But if I did, here’s what I’d say.

From the postmodern point of view, this is a text that needs to be deconstructed. It was obviously written by someone in a position of power pretending not to be. And by making light of the plight of blue collar workers, and allowing the oppressed workers to post this copy-machine meme in the workplace, this white-collar wolf in blue-collar sheep’s clothing has managed to persuade the oppressed workers that being powerless is something to be proud of.

Now, some of you young folks are too steeped in postmodernism to know anything about postmodernism, so let’s review. Postmodernism in its most vicious form started out with the notion that there exist various cultural constructs, or texts, or memes, that allow some human beings to oppress other human beings. Of course, in Soviet Russia it’s the other way around. Which is why they managed to deconstruct themselves, I guess.

Anyway, deconstructionism is all about throwing out the bad cultural memes, where “bad” is defined as anything an oppressed person doesn’t like. Which is fine as far as it goes, but the spanner in the works is that you can only be an oppressed person if the deconstructionists say you are. Dead white males need not apply. Fortunately, I’m not dead yet. Though I’m trying. As some of you know, several weeks ago I was in the hospital with a bleeding ulcer. I guess I’m a little like Soviet Russia. I oppress myself, so I deconstruct myself.

Oh, by the way, I got better. In case you hadn’t noticed.

Though I’m not allowed to drink anything brown anymore. Sigh. That’s why this speech is so boring — I wrote it under the non-influence.

But back to postmodernism. Postmodern critics have invented a notation for using a word and denying its customary meaning at the same time, since most customary meanings are oppressive to someone or other, and if not, they ought to be. Or something like that.

Anyway, I’m going to borrow that notation for my own oppressive purposes, and strike out a few of these words that don’t mean exactly what I want them to mean. I hope that doesn’t make me a postmodern critic. Or maybe it does. As Humpty Dumpty said, the question is who’s to be master, that’s all.

So let’s start by striking out “unwilling”, because there are quite a few willing people around here. Or at least willful.

And let’s strike out “unknowing” too, because you wouldn’t be sitting here listening to us leaders here tonight if you thought we didn’t know anything. On the other hand, maybe you just came for the jokes…

Now let’s strike out the “impossible”. Actually, I hesitate to strike that one out, because what we’re trying to do with Perl is to be all things to all people, and in the long run that is completely impossible, technically, socially, and theologically speaking.

But that doesn’t stop us from trying. And who knows, maybe more of it is possible than we imagine.

We definitely have to strike out ungrateful, because we know many people are grateful. Nevertheless, a number of people find it impossible to be grateful, and we should be working to please them as well. Love your enemies, and all that. Another impossible task. Or… perhaps the same one.

I like to please people who did not expect to be pleased. One day when I was a lot younger than I am now, I performed a piece on my violin. A lady came up to me afterward and said, “You know, I don’t like the violin. But I liked that.”

I treasure that sort of compliment, just as I treasure the email messages that say, “I had given up on computer programming because it wasn’t any fun, and then I discovered Perl.” That’s what I mean when I say we should work to please the people who don’t expect to be grateful.

Anyway, back to our Creed here. I can’t see anything wrong with the last two lines. In fact, they’re directly applicable.

We have done so much for so long with so little

That’s Perl 5.

We are now qualified to anything with nothing.

That’s Perl 6. I suppose I need to strike that out too, since it doesn’t really exist yet, except in our heads.

Well, maybe that’s not such a bad outline after all. Let’s talk a little more about those things.

> We the unwilling

> We the unwilling

Here in the open source community, we’re willing to help out, but that’s because we’re not willing to put up with the status quo. And that’s generally due to our inflated sense of Laziness, Impatience, and Hubris. But then a really funny thing happens. A number of us will get together and agree about something that needs doing because of our Laziness, Impatience, and Hubris, and then we’ll start working on that project with a great deal of industriousness, patience, and humility, which seem to be the very opposite qualities to those that motivated us in the first place.

I’ve tried to figure out a rationale for that, but I’ve pretty much come to the conclusion that it’s not rational or reasonable. It’s just who we are. Here’s a favorite quotation of mine.

“The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”

I think that all of us agree that this is true. We just can’t always agree on what to be unreasonable about. Of course, this was written by George Bernard Shaw, who had his own ideas of the most reasonable ways to be unreasonable. This is, after all, the guy who wrote Pygmalion, upon which the musical My Fair Lady was based, with dear old ‘Enry ‘Iggins and Eliza Dolit’le going at each other’s throats. And over linguistics of all things. Fancy that.

The only problem with this quote is that it’s false. A lot of progress comes from unreasonable women.

Well, okay, maybe Shaw meant “he or she” when he only said “he”. Still, if we’re going to please unreasonable people in the twenty-first century, maybe we need to rewrite it like this:

On the other hand, some people are impossible to please. We should probably just strike out "George Bernard Shaw" since he's a dead white male.

On the other hand, some people are impossible to please. We should probably just strike out "George Bernard Shaw" since he's a dead white male.

> We the unwilling, led by the unknowing

> We the unwilling, led by the unknowing

That’s me all over. Which is what the bug said after he hit the windshield.

Or as the bug’s friend said, “Bet you don’t have the guts to do that again.”

Whether I have the guts to do Perl again is another question. My guts are still in sad shape at the moment, according to the doctor…

Anyway, back to “me the unknowing”. I admit that there’s an awful lot that I don’t know. I’d love to tell you how much I don’t know, but I don’t know that either.

So I’ll have to talk about what I know instead. If you are so inclined, you may infer that I am totally oblivious to anything I don’t talk about today.

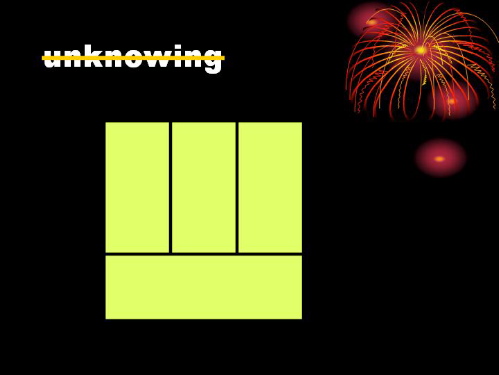

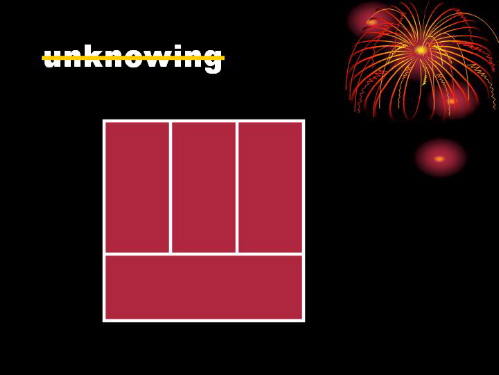

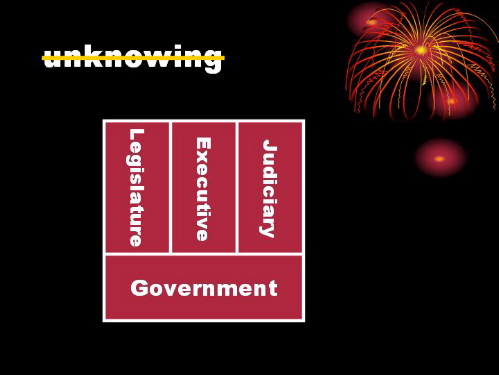

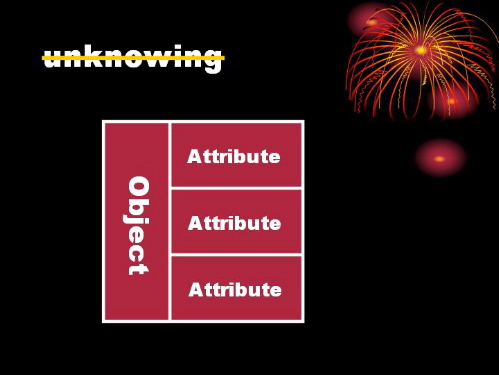

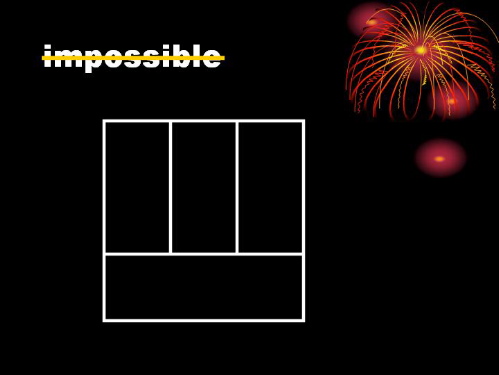

One thing I do know about is the universal architectural diagram. It looks like this.

It doesn’t have to be chartreuse. How about pink, to match the fireworks up in the corner. I put the fireworks up in the corner there in case you missed the fireworks on the 4th of July.

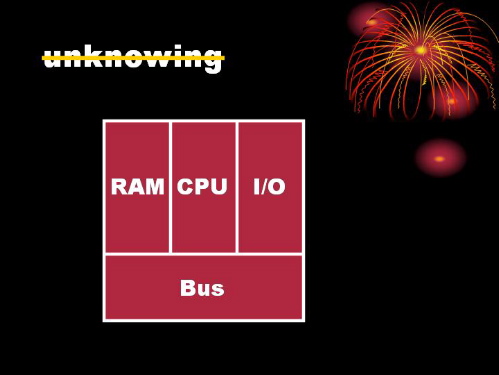

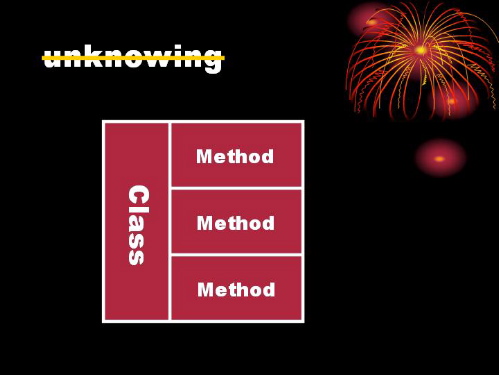

Anyway, this is the universal architectural diagram because you can represent almost any architecture with it, if you try hard enough. Here's a common enough one:

Anyway, this is the universal architectural diagram because you can represent almost any architecture with it, if you try hard enough. Here's a common enough one:

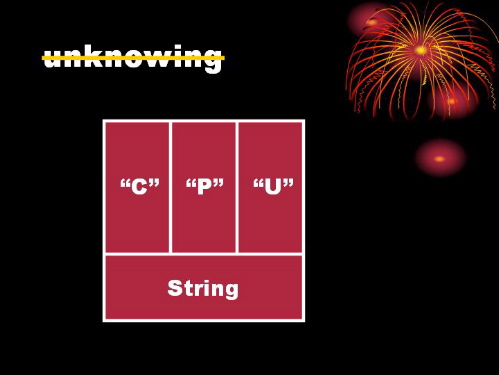

Here we have a bus that's common across the other three components of our computer, the memory, the CPU, and the I/O system. Within the computer we have other entities such as strings, which you can view either as a whole or as a sequence of characters.

Here we have a bus that's common across the other three components of our computer, the memory, the CPU, and the I/O system. Within the computer we have other entities such as strings, which you can view either as a whole or as a sequence of characters.

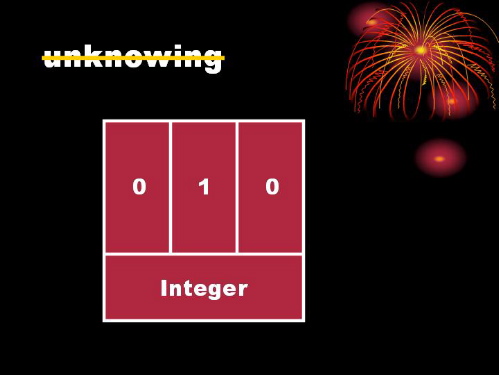

An integer is just like a string, only it's a sequence of bits.

An integer is just like a string, only it's a sequence of bits.

We can go from very small ideas like integers to very large ideas like government:

We can go from very small ideas like integers to very large ideas like government:

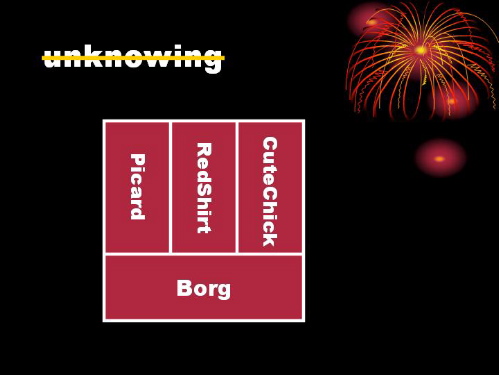

Or even alternate forms of government.

Or even alternate forms of government.

The diagram is even more versatile because you can rotate it on its side.

The diagram is even more versatile because you can rotate it on its side.

Now, for some reason, this particular orientation seems to engender the most patriotism. It might just be accidental, but if you color it like this

Now, for some reason, this particular orientation seems to engender the most patriotism. It might just be accidental, but if you color it like this

people start thinking about saluting it. Kinda goes with the fireworks, I guess.

people start thinking about saluting it. Kinda goes with the fireworks, I guess.

A little more dangerous is this diagram.

It's amazing how many people will salute that one. And people will even go to war for this one:

It's amazing how many people will salute that one. And people will even go to war for this one:

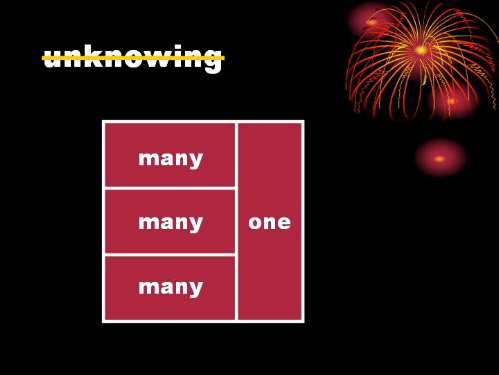

But you know, the whole notion of objects like this is that there are ways in which you treat them as a single thing, and ways in which you treat them as multiple things. Every structured object is wrapped up in its own identity. That's really what this little diagram is getting at.

But you know, the whole notion of objects like this is that there are ways in which you treat them as a single thing, and ways in which you treat them as multiple things. Every structured object is wrapped up in its own identity. That's really what this little diagram is getting at.

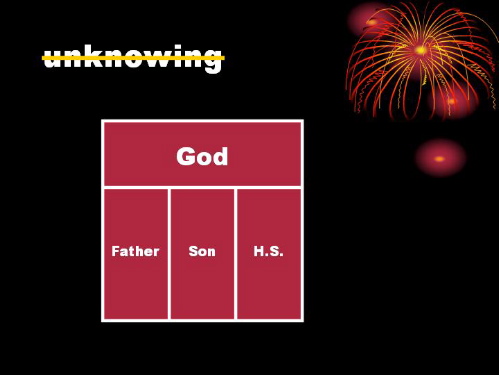

Well, let’s keep rotating it and see what we get.

Okay, if you happen to be a Christian of the trinitarian persuasion like me, then you believe that God is a structured object that is simultaneously singular and plural depending on how you look at it. Of course, nobody ever fights about that sort of thing, right?

Okay, if you happen to be a Christian of the trinitarian persuasion like me, then you believe that God is a structured object that is simultaneously singular and plural depending on how you look at it. Of course, nobody ever fights about that sort of thing, right?

It’s kind of unusual to see the diagram in this orientation, probably due to linguistic considerations.

It’s kind of unusual to see the diagram in this orientation, probably due to linguistic considerations.

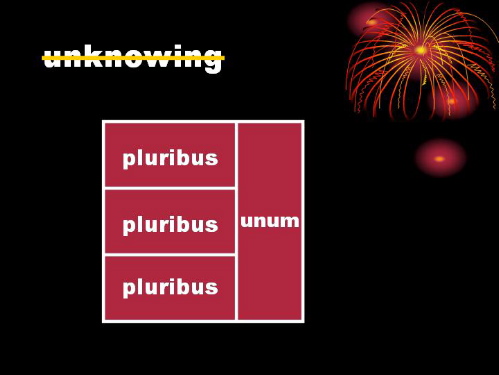

But whether you say "one out of many" or "e pluribus unum",

But whether you say "one out of many" or "e pluribus unum",

it means much the same thing. In a language that reads left to right, perhaps it's more naturally suited to processes that lose information, such as certain kinds of logic.

it means much the same thing. In a language that reads left to right, perhaps it's more naturally suited to processes that lose information, such as certain kinds of logic.

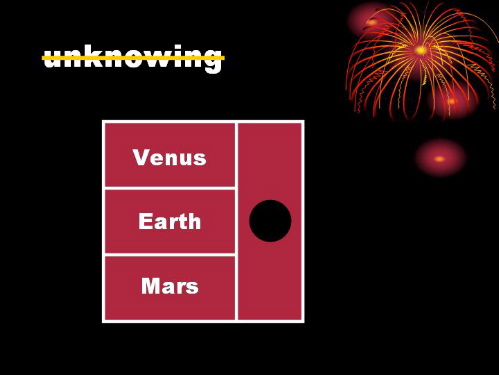

Again, we can go from the very small to the very large.

Again, we can go from the very small to the very large.

If you feed three random planets to a black hole, you also lose information. Or at least you hide it very well, depending on your theory of how black holes work.

If you feed three random planets to a black hole, you also lose information. Or at least you hide it very well, depending on your theory of how black holes work.

If you feed one of these diagrams to a black hole, it turns into a piece of spaghetti.

But let’s not, and say we did.

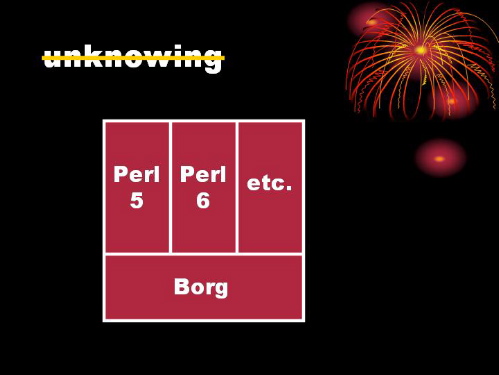

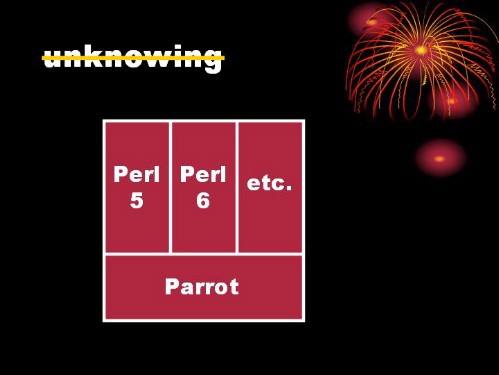

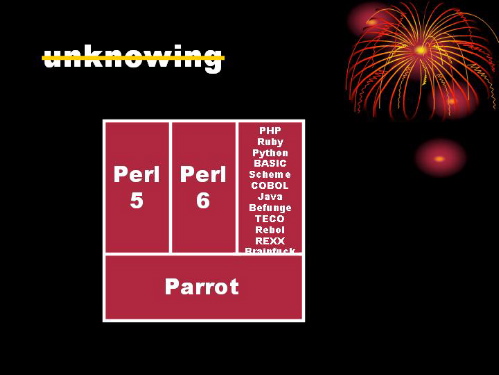

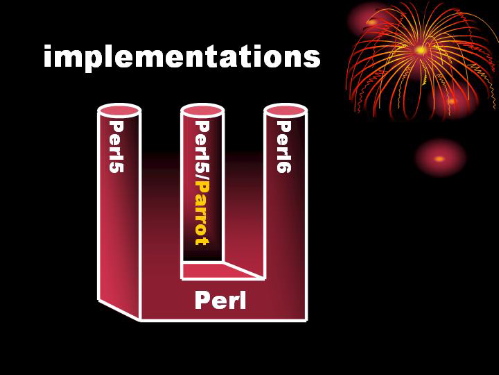

Oddly enough, what I’d really like to talk about today is Perl. If we look at our goal for the Parrot project, it looks something like this.

Oops, wrong slide.

Oops, wrong slide.

That is, Parrot is designed to be a single engine upon which we can run both Perl 5 and Perl 6. And... stuff. Admittedly, this is a rather Perl-centric view of reality, to the extent you can call this reality.

That is, Parrot is designed to be a single engine upon which we can run both Perl 5 and Perl 6. And... stuff. Admittedly, this is a rather Perl-centric view of reality, to the extent you can call this reality.

Well, okay, I’ll cheat and show you the other stuff we’d like to do.

We'd also like to support, for example, PHP, Ruby, Python, BASIC, Scheme, COBOL, Java, Befunge, TECO, Rebol, REXX, and... I can't quite make out that one on the bottom there. And if I could, I wouldn't say it anyway, because there are children present, and I wouldn't want to fuck up their brains.

We'd also like to support, for example, PHP, Ruby, Python, BASIC, Scheme, COBOL, Java, Befunge, TECO, Rebol, REXX, and... I can't quite make out that one on the bottom there. And if I could, I wouldn't say it anyway, because there are children present, and I wouldn't want to fuck up their brains.

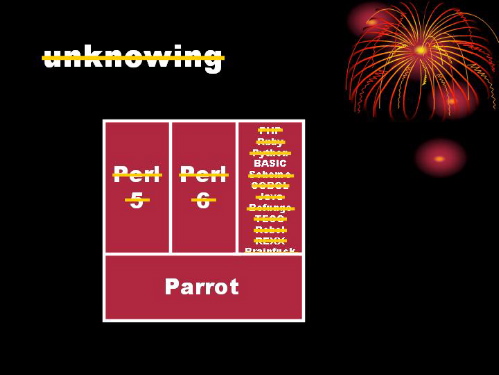

Okay, I admit this is not quite reality yet. I just put in all those languages because I’m a white male who is trying to oppress you before I’m quite dead. So I’d better strike out a few things that aren’t really there yet.

Could I interest you in a really fast BASIC interpreter?

Could I interest you in a really fast BASIC interpreter?

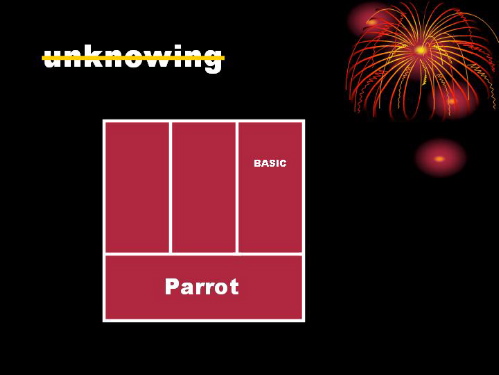

Well, it's time to move on to our next point.

Well, it's time to move on to our next point.

> We the unwilling, led by the unknowing, are doing the impossible.

> We the unwilling, led by the unknowing, are doing the impossible.

Is what we’re doing really impossible? It’s possible. But we won’t know till we try. More precisely, till we finish trying. Sometimes things seem impossible to us, but maybe that’s just because we’re all slackers.

And because we oversimplify.

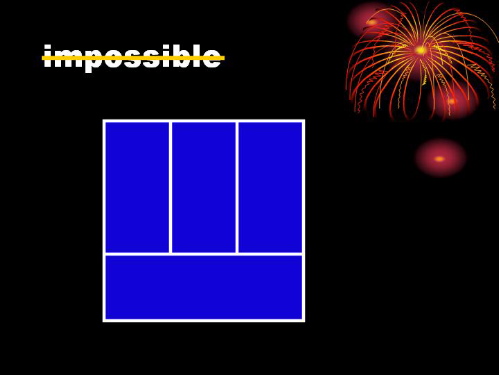

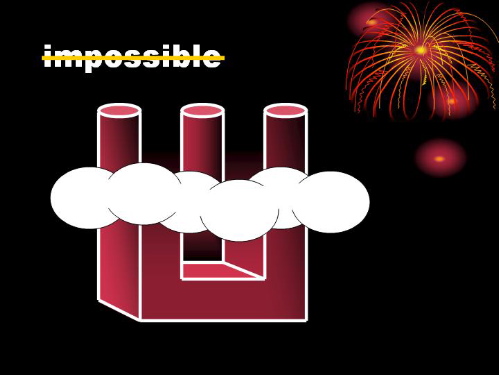

Let’s take another look at the pink tennis court. I mean, the universal architectural diagram. It really isn’t quite as universal as I’ve made it out to be. First, let’s get rid of the pink.

Maybe I should give equal time to blue.

Maybe I should give equal time to blue.

Nah.

Nah.

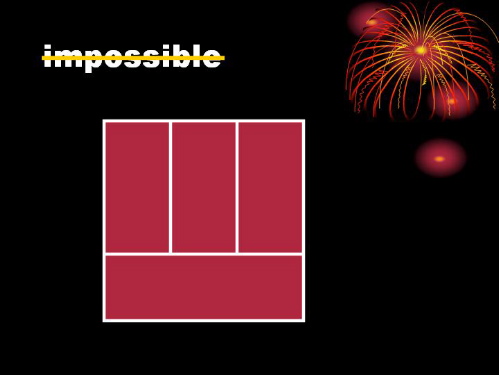

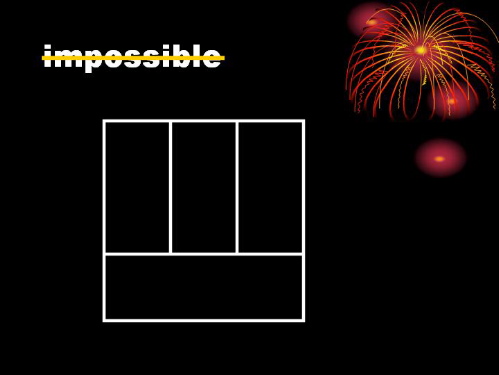

Anyway, as I was saying, this isn't universal enough. Here's the real universal diagram.

Anyway, as I was saying, this isn't universal enough. Here's the real universal diagram.

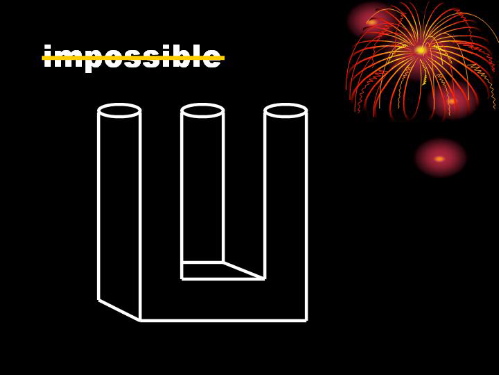

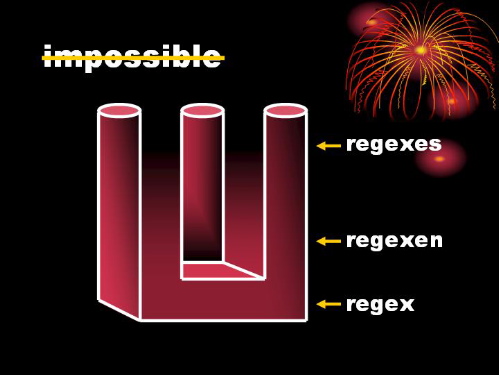

This is what's known as an impossible object. I like it. I'm impossible object oriented. This particular impossible object is often called a widget. But you knew that already.

This is what's known as an impossible object. I like it. I'm impossible object oriented. This particular impossible object is often called a widget. But you knew that already.

What you might not have known is that, up till now, it’s been thought impossible to color such an object accurately. But as you can see,

that is false. There are still some perceptual difficulties with it, but I'm sure *that* problem is just a relic of our reptile brain. Or was it our bird brain. I forget. In any event, if you have trouble perceiving this object correctly, just use the universal clarification tool.

that is false. There are still some perceptual difficulties with it, but I'm sure *that* problem is just a relic of our reptile brain. Or was it our bird brain. I forget. In any event, if you have trouble perceiving this object correctly, just use the universal clarification tool.

I'll assume you can supply your own cloud from now on.

I'll assume you can supply your own cloud from now on.

Should be easy here in Portland… I’m allowed to make jokes about Portland because I grew up in the Pacific Northwet.

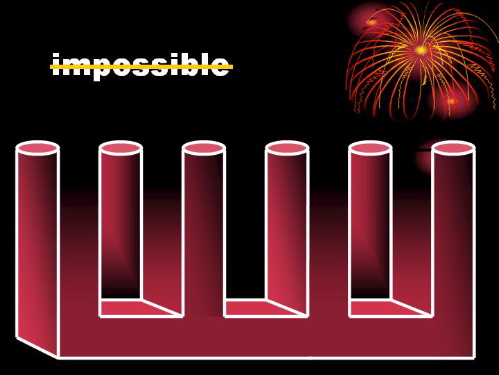

As you can see, this more accurate universal architectural diagram can actually be rotated in 3-d with properly simulated lighting.

It’s extensible.

It’s extensible.

Comb structures are important in a programming language. That’s why we’re adding a switch statement to Perl 6.

Comb structures are important in a programming language. That’s why we’re adding a switch statement to Perl 6.

It’s also a more accurate representation of Parrot.

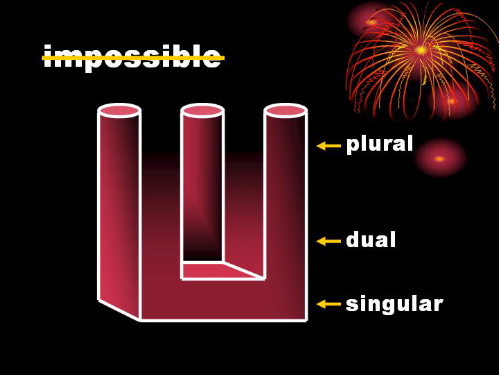

It's also more sophisticated linguistically.

It's also more sophisticated linguistically.

Not only can it represent singular and plural concepts, but also the old Indo-European notion of dual objects.

Not only can it represent singular and plural concepts, but also the old Indo-European notion of dual objects.

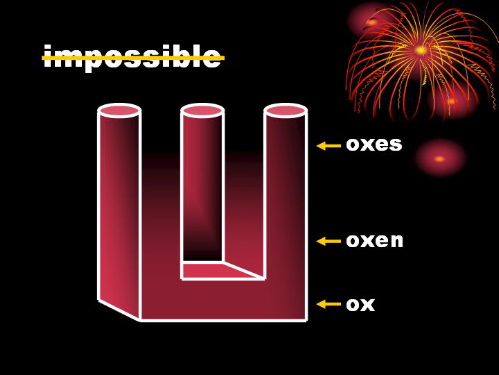

We still have vestiges of that in English.

One ox, many oxes, two oxen yoked together pulling your plow.

One ox, many oxes, two oxen yoked together pulling your plow.

Or one regex, many regexes, but two regexen working together.

Or one regex, many regexes, but two regexen working together.

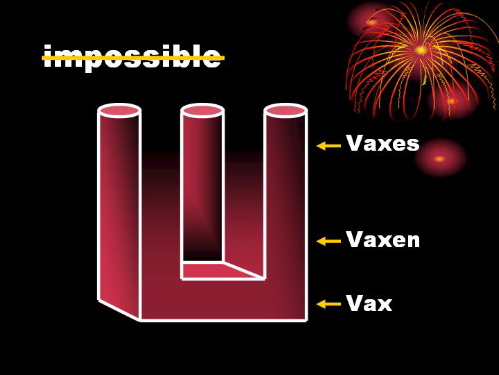

You always wanted to know the proper name for a two-headed Vax?

You always wanted to know the proper name for a two-headed Vax?

Everything is possible. You should be grateful.

On to the ungrateful undead.

On to the ungrateful undead.

There’s been a lot of carping lately about how slow Perl 6 development is going. Some of it comes from well intentioned folks, but some of it comes from our poison pen pals who live in the troll house. Still, I think a lot of the criticism shows a lack of understanding of the basic laws of development. These laws can be illustrated with this diagram:

Basically, perfect development is impossible. Development can be fast, good, and cheap. Pick two.

Basically, perfect development is impossible. Development can be fast, good, and cheap. Pick two.

Actually, that’s unrealistic.

Pick one.

Which one would you pick? You want fast? You want cheap? No, I think you want this one.

Good.

Good design is neither fast nor cheap. Every time we crank out a new chunk of the design of Perl 6 or of Parrot, it’s a bit like writing a master’s thesis. It’s a lot of reading, and a lot of writing, and a lot of thinking, and a lot of email, and a lot of phone conferences. It’s really complicated and multidimensional.

There's a lot going on behind the scenes that you don't hear about every day. Many people have sacrificed to give us time to work on these things. People have donated their own time and money to it. O'Reilly and Associates have donated phone conferences and other infrastructure. The Perl 6 design team in particular has borne a direct financial cost but also a tremendous opportunity cost in pursuing this at the expense of career and income. I'm not looking for sympathy, but I want you to know that I almost certainly could have landed a full-time job 20 months ago if I'd been willing to forget about Perl 6. I'm extremely grateful for the grants the Perl Foundation has been able to give toward the Perl 6 effort. But I just want you to know that it's costing us more than that.

There's a lot going on behind the scenes that you don't hear about every day. Many people have sacrificed to give us time to work on these things. People have donated their own time and money to it. O'Reilly and Associates have donated phone conferences and other infrastructure. The Perl 6 design team in particular has borne a direct financial cost but also a tremendous opportunity cost in pursuing this at the expense of career and income. I'm not looking for sympathy, but I want you to know that I almost certainly could have landed a full-time job 20 months ago if I'd been willing to forget about Perl 6. I'm extremely grateful for the grants the Perl Foundation has been able to give toward the Perl 6 effort. But I just want you to know that it's costing us more than that.

But Perl 6 is all about freedom, and that’s why we’re willing to pledge our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.

Times are tough, and I’m not begging for more sacrifice from you good folks. I just want to give a little perspective, and fair warning that at some point soon I’m going to have to get a real job with real health insurance because I can’t live off my mortgage much longer. It’s bad for my ulcer, and it’s bad for my family.

Fortunately, the basic design of Perl 6 is largely done, appearances to the contrary notwithstanding. Damian and I will be talking about that in the Perl 6 session later in the week.

Well, enough ranting. I don’t want to sound ungrateful myself, because I’m not. In any event, the last three years have been extremely exciting, and I think the coming years will be just as interesting.

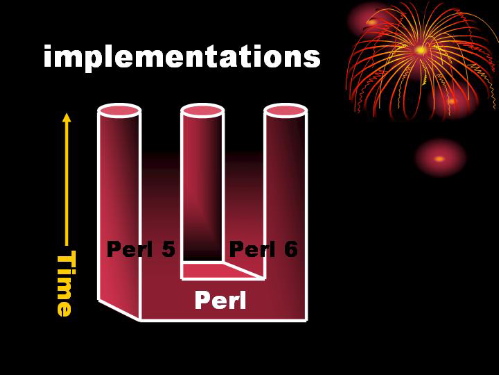

In particular, I have a great announcement to make at the end of my talk about what’s going to be happening next. But let me explain a bit first what’s happened, again using our poor, abused widget.

In this case, time is flowing in the upward direction.

In this case, time is flowing in the upward direction.

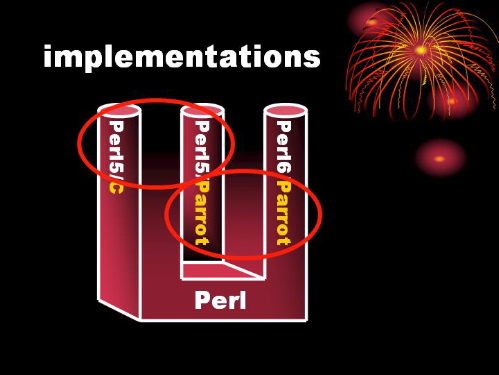

Originally we just had one implementation of Perl, and the general perception as we started developing Perl 6 was that we were going to have two implementations of Perl.

But in actual fact, we’re going to have at least three implementations of Perl.

First, the good old Perl 5 that’s based on C, And on the right, the Perl 6 that’s based on Parrot. But there in the middle is a Perl5 that is also based on Parrot.

Note that the left two are the same language, while the right two share the same platform.

Note that the left two are the same language, while the right two share the same platform.

So what’s that Perl 5 doing there in the middle? If you’ve been following Perl 6 development, you’ll know that from the very beginning we’ve said that there has to be a migration strategy, and that that strategy has two parts. First, we have to be able to translate Perl 5 to Perl 6. If that were all of it, we wouldn’t need the middle Perl there. But not only do people need to be able to translate from Perl 5 to Perl 6, it is absolutely crucial that they be allowed to do it piecemeal. You can’t translate a complicated set of modules all at once and expect them to work. Instead, we want people to be able to run some of their modules in Perl 5, and others in Perl 6, all under the same interpreter.

So that’s one good reason to have a Perl 5 compiler for Parrot. Another good reason is that we expect Perl 5 to run faster on Parrot, by and large.

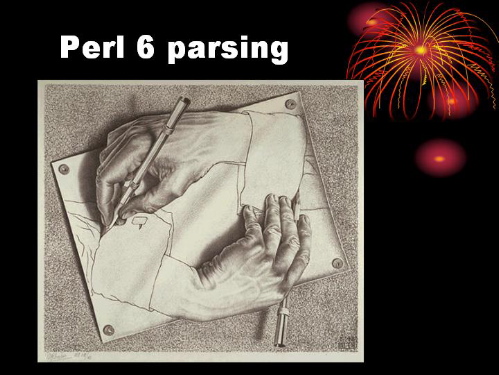

Yet another reason is that we have a little bootstrapping issue with the Perl 6 grammar. The Perl 6 grammar is defined in Perl 6 regexes. But those regexes are parsed with the Perl 6 grammar. Catch 22. The solution to this involves two things. First, a magical module of Damian's that translates Perl 6 regexes back into Perl 5 regexes. Second, a Perl 5 regex interpreter to run those regexes. Now, it'd be possible to do it with old Perl 5, but it'll be cleaner to run it with the new Perl 5 running on Parrot.

Yet another reason is that we have a little bootstrapping issue with the Perl 6 grammar. The Perl 6 grammar is defined in Perl 6 regexes. But those regexes are parsed with the Perl 6 grammar. Catch 22. The solution to this involves two things. First, a magical module of Damian's that translates Perl 6 regexes back into Perl 5 regexes. Second, a Perl 5 regex interpreter to run those regexes. Now, it'd be possible to do it with old Perl 5, but it'll be cleaner to run it with the new Perl 5 running on Parrot.

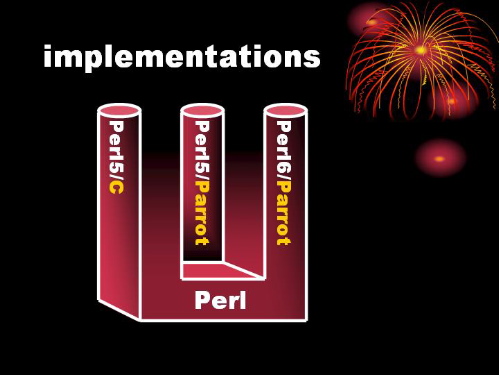

Now, it's awfully cumbersome to keep saying "Perl 5 over Parrot" and such, so we need to do some namespace cleanup here. We can drop the "over Parrot" for Perl 6, because that's redundant.

Now, it's awfully cumbersome to keep saying "Perl 5 over Parrot" and such, so we need to do some namespace cleanup here. We can drop the "over Parrot" for Perl 6, because that's redundant.

Likewise, people always think of the original when we say "Perl 5".

Likewise, people always think of the original when we say "Perl 5".

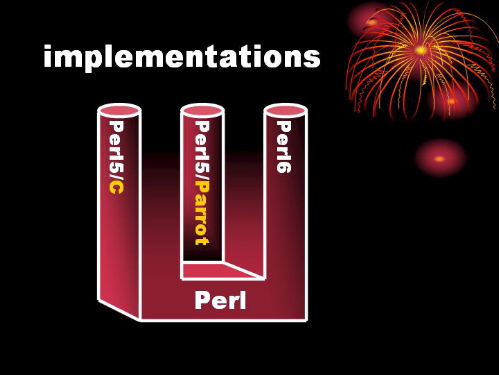

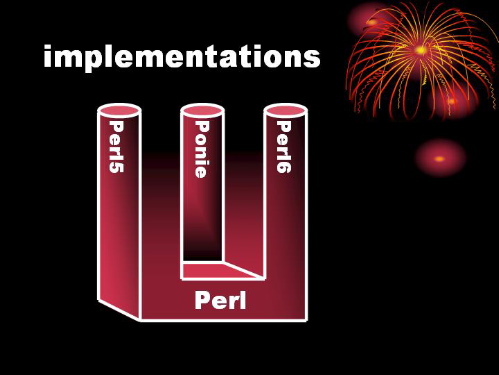

That means we need a code name for this thing in the middle. We've decided to call it "Ponie".

That means we need a code name for this thing in the middle. We've decided to call it "Ponie".

We have lots of reasons to call it that. To be sure, none of them are *good* reasons, but I'm told it will make the London.pm'ers deliriously happy if I say, "I want a Ponie".

We have lots of reasons to call it that. To be sure, none of them are *good* reasons, but I'm told it will make the London.pm'ers deliriously happy if I say, "I want a Ponie".

And I do want a Ponie. “I want the Ponie, I want the whole Ponie. I want it now.”

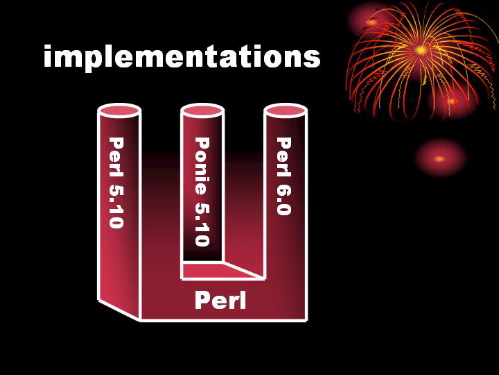

The plan is to for Ponie version 5.10 to be a drop-in replacement for Perl 5.10. Eventually there will be a Ponie 5.12, and if Ponie is good enough, there may not be an old-fashioned 5.12. We'll just stop with 5.10.

The plan is to for Ponie version 5.10 to be a drop-in replacement for Perl 5.10. Eventually there will be a Ponie 5.12, and if Ponie is good enough, there may not be an old-fashioned 5.12. We'll just stop with 5.10.

So we’re gonna start on Ponie right now. Since I’ve been carping about lack of resources, you might wonder how we’re gonna do this.

Well, as it happens, a nice company called Fotango has a lot of Perl 5 code they want to run on Parrot, and they are clued enough to have authorized one of their employees, our very own Arthur Bergman, to spend company time porting Perl 5 to Parrot.

Is that cool or what? I’m out of time, so read the press release. But I’m really excited by our vision for the future, and if you’re not excited, maybe you need to have your vision checked.

Thanks for listening, and I hope that from now on you'll all be completely unreasonable.

Thanks for listening, and I hope that from now on you'll all be completely unreasonable.

Tags

Feedback

Something wrong with this article? Help us out by opening an issue or pull request on GitHub