Building a Finite State Machine Using DFA::Simple

I am converting some articles from MS Word to HTML by hand. I often use bulleted outlines so I face a lot of work creating lists with nested sub-lists. It didn’t take opening and closing many <ul> and <li> tags to realize I wanted to automate the task.

It’s very easy to use filters with my text editor and I’ve written several in Perl to speed up my HTML formatting. I decided to create a filter to handle this annoying chore. After a little thought I decided the logic involved was just tricky enough to use a finite state machine (FSM) to keep things straight.

Large programs always require some thought and planning while most small programs can be written off the top of the head. Once in a while I run into a small problem with just enough complexity that I know “off the top” will quickly become “not so quick, very dirty, and probably wrong.” Finite state machines can help to solve these knotty problems cleanly and correctly.

There have been several times I wanted to use an FSM but didn’t because I lacked a good starting skeleton. I would do it some other way or hand code an FSM using a loop, nested if statements, and a state variable. This ad hoc approach was tedious and unsatisfying.

I knew there had to be a Perl module or two implementing FSMs and decided it was time to add this tool to my toolbox.

What Are Finite State Machines?

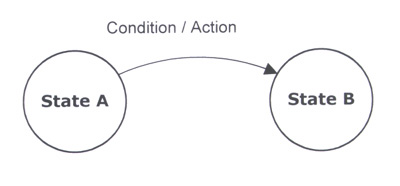

A finite state machine is a set of states, one of which is the starting state. Each state has a set of transitions to other states, based on the next input token. A transition has a condition and an action. If the condition is met, the FSM performs the action and then enters the new state. This cycle repeats until reaching the end state.

Finite state machines are important in the theory of computation. A Wikipedia article on finite state machines goes into the computer science aspect. FSMs are valuable because it is possible to identify precisely what problems they can and cannot solve. To solve a new class of problems, add features to create related machines. In turn, you can characterize problems by the kind of machine needed to solve it. Eventually you work up to a Turing machine, the most theoretically complete computing device. It is a finite state machine attached to a tape with potentially infinite capacity.

The formal and highly abstract computer science approach to FSMs does not hint at their usefulness for solving practical problems.

The Bubble Diagram

Figure 1 shows the parts of a finite state machine. The circles represent states. A double circle indicates the start state. The arcs represent the transitions from one state to another. Each arc label is a condition. The slashes separate actions.

Figure 1. Finite state machine elements.

Figure 1. Finite state machine elements.

I like FSMs because they are graphical. I can grab a pen and sketch the solution to a problem. The bubble diagram helps me see the combinations of states and input conditions in a logical and organized way.

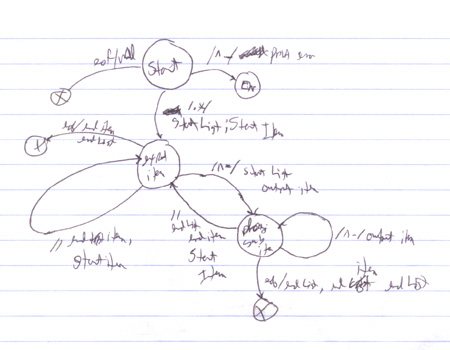

Figure 2. Initial rough diagram.

Figure 2. Initial rough diagram.

Figure 2 is the initial diagram I drew for the HTML list problem. The diagram turned out to be have an omission — it does not handle blank lines. Having discovered this bug, it was easy to make sure to consider blank lines in every state.

Figure 3. The final diagram.

Figure 3. The final diagram.

Figure 3 is a formal diagram of the final FSM, complete with blank-line handling, prepared for this article. Normally, I would never be so elaborate for such a small problem. You can see that it is an excellent way to communicate a solution to others.

Looking at DFA::Simple

I have yet to look for a Perl module to do something and come up totally empty handed. That’s absolutely my favorite thing about Perl.

I looked for existing FSM modules and found DFA::Command and DFA::Simple. DFA::Command looks good but was more than I needed. (By the way, the simplest FSM is also a “deterministic finite automata,” thus the DFA in the module names.)

The “simple” in DFA::Simple sounded promising, but the module’s documentation is poor. The sample program is difficult to follow and does not process input from a file. Using the module in the real world is left as an exercise for the reader: the docs do not mention handling errors and the end-of-file condition.

While FSMs start as circles and arcs, they end up as tables of states and transitions. My interest was in exactly how the packages created these tables. Having clean, easy-to-look-at code is very important to me. I’m probably the one who’ll have to change it someday!

I was very unhappy that DFA::Simple defines its sample FSM in a position-dependent way. The state being defined depends upon its textual position in the source. It uses numeric constants for state IDs within the tables and you must synchronize them with any changes. Comments indicate which state number you think you are working on, but they could easily unsynchronize as you add, drop, and move states.

To clarify, I saw this:

my $states = [

# State 0

[ ...jump to state 2... ],

# State 1

[ ...jump to state 0... ],

# State 2

[ ...jump to state 1... ],

# ...

];

But I wanted to see something like this:

my %states;

$states{stStart} = [ ...jump to stSubitem... ];

$states{stItem} = [ ...jump to stStart... ];

$states{stSubitem} = [ ...jump to stItem... ];

# ...

This was a big negative. I have run into enough bugs caused by position-dependency that I refused to consider using this code. I almost decided to write my own module, but first went back and took a last look at DFA::Simple to see if there was any way I could make it work.

I realized that an FSM use symbolic constants for state definitions. Array references using these symbolic constants would provide the self-documenting and maintainable approach I demanded. It was easy to develop a way to process input (handling errors and EOF) that works in most cases. I put it together, gave it a try, and it worked!

The Input and Output

The input comes from copying an MS Word document and pasting it into my text editor. My bulleted outlines look like this:

o Major bullet points

- each line is a point

- a leading "o " is removed

o Minor bullet points

- indicated by a leading "- "

- may not start a list

- only one level of minor points is supported

o Future enhancements

- numbering of points

- handling of paragraphs

o Start a new group of points

- a blank line indicates end of old group

- old group is closed, new one opened

This outline actually documents key features of the program.

A correctly nested HTML list must come entirely within the parent list item. This is what made the filter tricky enough that I wanted to use a finite state machine. When you open a top-level list element you have to wait for the next input to see if you should close it or start a sub-list. When you look at an input, you have to know if you have an open list element pending. The current state and the input determine what to do next, exactly fitting the finite state machine model.

A snippet of output:

<ul>

<li>Major bullet points

<ul>

<li>Each line is a point</li>

<li>A leading "o " is removed</li>

</ul>

</li>

...

</ul>

Not being an HTML expert, I initially tried to insert my sub-list between two higher-level list elements. The page rendered correctly but would not validate, revealing my error and starting this project.

The Parts of the Machine

The first step in building the machine was deciding how to represent state names symbolically rather than numerically. The natural choice is the constant pragma.

use constant {

stStart => 0,

stItem => 1,

stSubItem => 2,

stEnd => 3,

};

I defined the machine as two arrays. The first is @actions defining what to do when entering and exiting a state. You might use it to initialize a data structure on entry and save it on exit, or allocate resources on entry and de-allocate them on exit.

Each element of @actions is a two-element array. The first is the enter action and the second the exit action. My program logs a message on entry and leaves the exit action undefined.

my @actions;

# log entry into each state for debugging

$actions[stStart] = [sub{print LOG "Enter Start\n";} ];

$actions[stItem] = [sub{print LOG "Enter Item\n";} ];

$actions[stSubItem] = [sub{print LOG "Enter SubItem\n";}];

$actions[stEnd] = [sub{print LOG "Enter End\n";} ];

Each element of the second array, @states, is an array of transitions for a state. A transition has three elements: the new state; the test condition; and the action. The condition is a subroutine returning true or false, or undef, which always succeeds.

The machine tests the transitions of the current state in sequence until a condition returns true or is undefined. Then it takes the action and enters the new state. If the new state is different than the old one, the respective exit and entry actions execute.

As with the final else in a nested if statement, consider having an undef at the end of the transitions. If nothing else, log a “can’t happen” error message to catch holes in your logic as well as holes caused by future changes.

Here is the transition array for a state:

my @states;

# Next State, Test, Action

$states[stSubItem] = [

[stEnd, sub{$done}, sub{end_sublist; end_list} ],

[stSubItem, sub{/^-\s/}, sub{output_subitem} ],

[stStart, sub{/^$/}, sub{end_sublist; end_list} ],

[stItem, undef, sub{end_sublist; start_item}],

];

This uses the symbolic constants for state IDs in both tables. The states’ numerical values are irrelevant. I followed convention and numbered the states consecutively from zero, but I tested the program using random state numbers. It worked fine.

This is much better than the definition of the sample FSM in DFA::Simple. Now adding, deleting, and shuffling states will not introduce position-dependent bugs.

Final Assembly

The parts of the machine are built. Assembling them is easy:

use DFA::Simple

my $fsm = new DFA::Simple \@actions, \@states;

$fsm->State(stStart);

This creates a new DFA::Simple object using references to the @actions and @states arrays. The State method retrieves or sets the machine’s state, invoking entry and exit routines as needed. Here, the call sets the initial state.

Putting the Machine in Motion

The major goal of this project was to develop a skeleton to develop FSMs quickly, with an emphasis on filters. I wanted to develop a way of handling file input and processing errors that would work for future projects.

This loop accomplishes that:

while (<>) {

chomp;

# log input line for debugging

print LOG "Input <$_>\n";

# trim input and get rid of leading "o "

s/^\s+//;

s/\s+$//;

s/^o\s+//;

# process this line of input

$fsm->Check_For_NextState();

# get out if an error occurred

last if $error;

}

The while (<>) loop is standard for filters. The application cleans up input as needed. In this case, it chomps each line and trims and strips it of some text bullet characters.

The log message is for initial debugging. This, along with the new state message, gives a clear picture of what is happening.

The most important statement is $fsm->Check_For_NextState();, which does the major work — scanning the current state’s transition table to see what to do next.

The FSM must be able to exit early if it spots an error. This requires the use of a global $error switch. It starts out as false. If $error is true, the program ends and returns the value of $error.

End-of-file handling also uses a global switch, $done. It is initially false and changes to true when the program exhausts standard input. One last cycle runs to give the machine a chance to clean up. Transition conditions checking for EOF can simply return $done.

Here is the end-of-file code:

unless ($error) {

# finish up

$done = 1;

$fsm->Check_For_NextState();

}

The program does not support early normal termination. You can enter a state with no transitions and the program will read (but ignore) any remaining input. However, there is no way to avoid reading all of the input without setting $error. You can implement early exit by adding a $exit switch and handling it similarly to $error.

Appropriately for filters, this program is line oriented. Many FSMs read input a character at time: lexical scanners and regular expression parsers, for example. This program could easily change to handle character input.

The Action Routines

Now that the machine is purring along, it needs to do something. This is the purpose of the actions. Those in my program are typical of a finite state machine. They invoke small subroutines that form a mini-language for building lists with sub-lists. The subroutines are very simple, but running them in the right order does the job.

Thus, this approach breaks a complex problem into smaller pieces, each of which is simply solvable. This is what programming is all about.

Conclusion

The next time you have a knotty little problem like this one, try sketching a solution using a bubble diagram and implementing it with DFA::Simple. You’ll have added a great new tool to your toolbox.

Resources

- Zipped source code of the final program

- Finite State Machines at Wikipedia

- Turing Machines at Wikipedia

- DFA::Simple at CPAN

- DFA::Command at CPAN

- Finite State Technology at Xerox Research Centre Europe

- Finite State Utilities in C++ by Jan Daciuk

Tags

Feedback

Something wrong with this article? Help us out by opening an issue or pull request on GitHub